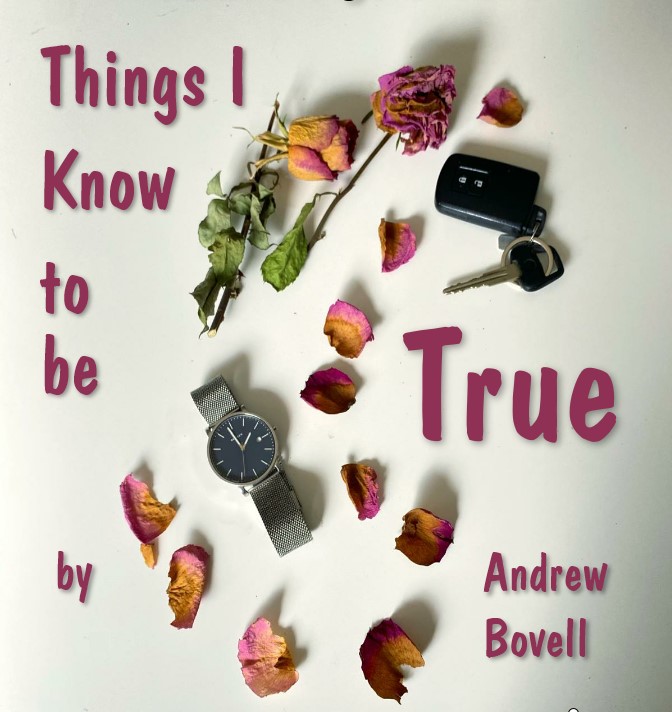

Things I Know to be True

By Andrew Bovell

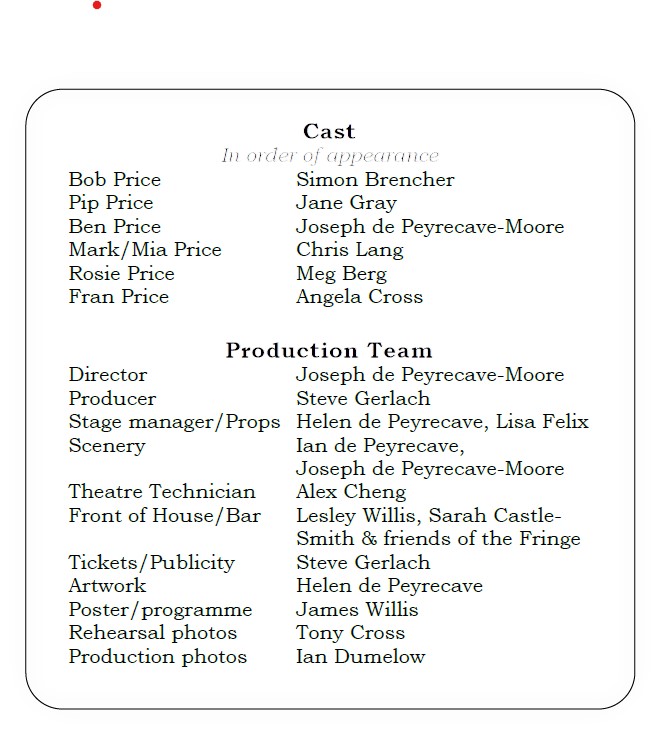

Directed by Joseph de Peyrecave-Moore. November 2025

Photos by Ian Dumelow

REVIEW: "There is something rather special about Alton Fringe Theatre...

...Just as the pantomime season is getting under way, they eschew mere “entertainment” and present a serious and moving contemporary drama exploring the deep bonds uniting the members of one family – and the equally deep fault lines that divide them.

The latest in a long line of powerful productions from the Fringe was Andrew Bovell’s Things I Know to be True, first performed in 2016. The action is set in Bovell’s native Australia, but minimal textual changes were required to switch to an English setting. The cast of six included some familiar Fringe stalwarts and some refreshingly new, younger actors. All were stunningly good. The set in Alton College’s Wessex Arts Theatre was sparse but symbolic: the oranges in the fruit bowl were perhaps an oblique allusion to Jeanette Winterton who treated similar issues in her most famous novel, and the roses in the garden spoke of idealised love. The Leonard Cohen songs played before the start evoked just the right mood.

The play, whilst modern, explores a theme as old as drama itself, so it was entirely fitting that the opening tableau should remind us of the chorus in a Greek tragedy. It hinted at a subsequent tragic death of one of the children. Then we meet the youngest member of the Price family, Rosie. Meg Berg captured perfectly the starry-eyed idealism, the yearning for romance on her gap-year European travels, and the naïve vulnerability of this character. Having been abandoned and robbed in Berlin by her three-day lover she wants only to go home to her family, realising how little she knows about life.

We then meet Bob and Fran, the parents. Simon Brencher and Angela Cross conveyed touchingly the humdrum reality of domestic life built around their children in whom both have invested so much of themselves (“I stayed because of the kids”, Fran later admits). Banal bickering continues when Rosie appears, and, as happens throughout, first one parent turns mediator whilst the other remains critical or angry, then these roles are reversed. They are both loving parents who try to understand their children…

The other (grown-up) children soon arrive. First Pip, the busy professional woman and mother of two who has fallen out of love with her husband. Jane Gray brought energy and self-confidence to her role, whilst leaving the audience in no doubt that she, just as much as her younger sister, was still seeking fulfilment. Then Ben, the financier, played by director Joseph de Peyrecave-Moore, equally in a hurry, equally intense. Then Mark, who has recently split up with his girlfriend and who does not want to talk about it: Chris Lang responded with great sensitivity to the task of portraying a man increasingly uncomfortable in his own body. He too wanted to move on (“I can’t stay.”) This lively pace was maintained throughout. So all four siblings are very different, but all were shown to be dissatisfied with their current lives and feeling misunderstood by their parents. This tension was maintained until the very end of the play and made the more reflective, nostalgic monologues particularly poignant.

There followed a series of personal crises, and the emotional temperature grew ever higher, but all six actors owned their characters so assuredly that we never stopped believing in them and empathising with them. Pip announces she is leaving her husband, much to the chagrin of her parents. Then Mark reveals, awkwardly, that he wants to undergo a sex change. The touching previous scene had shown Bob and Fran reluctantly accept the idea that their son was gay, but that he should wish to transition is quite beyond them. The balance between sympathy for Mark’s plight and for his parents’ inability to accept his proposed solution was finely managed. As in all the best drama, the audience was led to engage with both parties, and to judge for themselves. These were complex issues with no easy resolution, but underlying all the thorny inter-family relations was a mutual love: Bob kisses Mark in farewell at the airport in a moment of beautifully controlled pathos. Finally, Ben confesses to having stolen money at work: the roll of his eyes when his father doesn’t understand the meaning of “skimming” was one of numerous hints at mutual incomprehension, and his attempt at self-justification enrages his father, but here again the other parent, Fran, comes to the rescue with a plan for redemption.

The parents are eventually left all alone at home, even Rosie having fled the nest. They try to distract themselves from the emptiness. Fran goes off to work, and the phone rings, in an abrupt repeat of the opening scene. Pip, Ben, and Mark (now Mia) respond to the tragic news in a way that emphasises their shared ties (“Please, God. Not her”) while Rosie tells of how their mother was killed in a car crash after falling asleep from worry and exhaustion. So it was not one of the children at all. Rosie is a little older and has put her personal disappointment in perspective. Life goes on. There cannot have been a dry eye in the house. It was a deeply moving finale, drama at its very best.

Many thanks and congratulations to director Joseph de Peyrecave-Moore and his entire team for this powerful, memorable production. The major production for next year is likely to be Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Forget Claudia Winkleman: this is the Fringe that matters. Come. See. And be conquered.

Peter Allwright